Coping with Cortisol

The unseen link between well-being and performance

Our ability to perform is in part dependent on how well we feel. And yet, our state of well-being and health is governed by an inner ‘clock’ that follows the Circadian Rhythm, a 24 hour cycle based on the rise and fall of the sun. All living things are affected by this cycle - plants, bacteria, viruses, animals and our own biological processes. It determines when we wake, sleep and drives the biological processes that keep us alive and vital.

So how can we optimise our performance when the very biological processes that drive us, seem to be beyond our control?

This article explains how to regulate cortisol secretion, a key element of the Circadian cycle and what you can do to enhance your performance by regulating your body clock.

We feel happier when our life style is in synch with this natural rhythm, however, most of us have live styles that force us to live out of synch with it. Ultimately, this interferes with the natural sequence and timing of our biological processes, making it harder for them to work in the harmony required to maintain optimal mental and physical health and a state of well-being that peak performance requires.

A range of symptoms can begin to appear when a disturbed rhythm becomes a chronic state. These range from an inability to focus or concentrate, to a host of mental and physical illnesses that need medical treatment.

Compounding the situation is that it also becomes harder to get the quality of sleep needed for the body to repair itself and to feel refreshed. Starting the day tired and in an increasing state of disrepair makes it impossible to function at our best.

Diagram 1. The Circadian Rhythm

Cortisol, the stress hormone, rises and falls as part of this Circadian Rhythm. Cortisol is not ‘bad’, it’s actually crucial to being alive. It helps us to wake up in the morning and gives us the ability to focus on tasks. Without it we’d die.

Too much of it though, and disease takes root. It is therefore important to help our bodies maintain the ‘Goldilocks’ level of cortisol needed to optimise performance and maintain a state of well-being. Here we will suggest self-care practices that will help you to do this.

Notice in Diagram 1, how cortisol levels rise and fall over a 24 hour period. It increases rapidly when it is time to wake up. It then drops throughout the day until it is time for us to go to sleep.

The highest cortisol levels coincide with our peak alertness, around 9 am. It then steadily declines over the day, making us less alert. This causes an afternoon slump and the post lunch ‘grave yard shift’, dreaded by most conference presenters.

As our cortisol levels continue to drop away, we gradually find ourselves winding down, ultimately to the point where we want to sleep. This is our natural body rhythm.

Unfortunately, today’s work and life styles are rarely in synch with this. Instead, it is expected that we should stay focused and perform consistently throughout the day. And even into the evening. Working late, often leaves us feeling ‘wired and tired’ as we approach bed time. This happens because our cortisol level has increased, just when we need it to be at it’s lowest. We then find it hard to fall asleep.

Light is a key factor in this. Our computer and phone screens emit blue light, which tells the brain that it is daytime. This causes a shift in our rhythm which postpones the drop in cortisol needed for us to fall asleep. TV, especially in the bedroom has the same effect.

Gradually, the cortisol tide rises again which causes us to wake up. But, if our cortisol levels rise prematurely, this will interfere with us experiencing a full and restorative sleep.

In Diagram 1, when waking up at around 3 am, we lose out on the period of sleep needed for psychological repair - the integration of the day's learning and memory consolidation. This period of sleep is an key factor in sustaining mental well being and the ability to think clearly.

A research experiment demonstrated how sleep deprived people perform at a similar level to people who are slightly drunk.

Symptoms of chronic cortisol often include sluggishness and finding it hard to concentrate or stay focused. It may take longer to think things through. We may make more mistakes and have to spend more time double-checking and correcting what we have done. In short, it becomes harder to be efficient at getting work done. As our performance drops, we then have to work harder to compensate for the inertia created by lack of deep sleep.

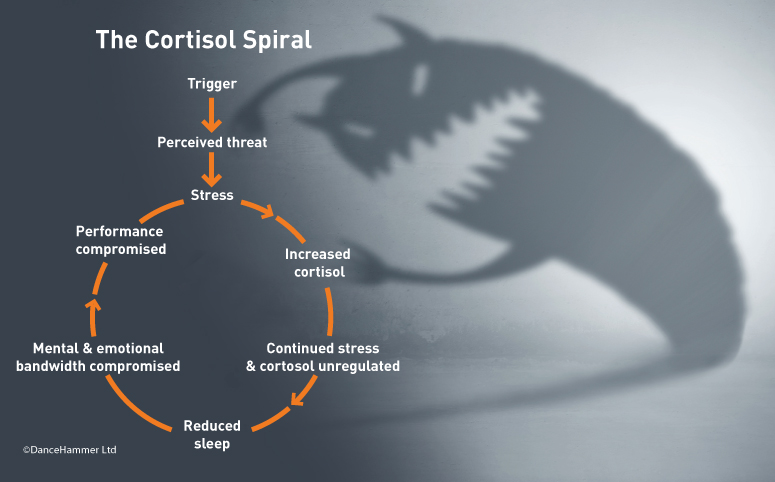

This can trigger a performance spiral (Diagram 2). The performance slump may increase stress levels, causing us to produce yet more cortisol, making it even harder to get the sleep and rejuvenation that only results when our body processes are in harmony.

When high levels of cortisol becomes a chronic state of normality, it can effectively raise the entire length of the cortisol tide. Our daily rhythm then becomes so distorted that it seeds a range of health issues due to many of our essential biological processes no longer occurring in a timely, inter-related manner.

Early signs could include exhaustion and depression, but ultimately this will cause chronic inflammation, the precursor to a vast range of physical problems.

Diagram 2. The Cortisol Spiral

Cortisol in a nutshell

Just to be clear, cortisol is not the villain, here. Too little cortisol (Addison’s disease) and we become sluggish, unable to think and act clearly. We may experience dizziness, muscle loss, general weakness, nausea. Low cortisol also affects our healthy response to stress and reduces our immune response to viruses and disease. In the case of a severe crisis of cortisol deficiency it can even lead to a coma and ultimately, death.

The more common issue though, is too much cortisol. When we become ‘wired’ we are unable to settle, relax and sleep. We then become vulnerable to disorders such as depression, irritability or even aggression. Inflammation, a known precursor to many diseases, can set in. We can also experience a range of problems such back ache, anxiety, bowel issues, impaired ability to concentrate, helplessness, panic, asthma and more. A chronic excess of cortisol gives rise to Cushing’s syndrome.

It is important that we take proactive action, especially during times of prolonged stress, so that we can more effectively manage the cortisol secretion that is triggered when our threat response is activated. If we don’t, we may likely discover that our mental and emotional bandwidth becomes deeply compromised, making us less able to tolerate challenging relationships and situations. Our performance as a leader and team member then declines.

We might become grumpy and on a ‘short fuse’. We may even become downright aggressive. When this is out of character, its a clear sign that the balance of our natural rhythm has become significantly disturbed.

It should be clear, that at this point, our ability to perform has become severely compromised. This is particularly bad news for leaders who’s team needs them to be on their best game.

Because this cortico-Cricadian deterioration is a gradual one, it can be hard for a person to realise that it is happening to them. It may require a kind conversation from someone to help them recognise that they have been sliding away from feeling and being optimal.

Luckily our bodies have in-built mechanisms for maintaining healthy hormonal levels, but there are steps we can take that will make it easier and quicker for the body to return to a state of balance. This will be explored once we highlight the hormones responsible for keeping our Circadian Rhythm in check.

Melatonin - the sleep hormone

Melatonin plays a key role in managing our well-being. It is produced naturally in the body and helps to regulate the cortisol tide and maintains a healthy Circadian Rhythm. Its level rises and falls in the opposite phase to cortisol secretion, ‘peaking’ when cortisol is at its lowest ebb, and vice versa. Without melatonin, it would be harder to drift off and to stay asleep long enough to feel restored.

Melatonin has an addition range of functions. It contributes to energy metabolism, functioning of the immune system, inhibits oxidative stress and participates in the ageing process.

As we age, our bodies produce less melatonin and so many of us may find that we don’t have as much as our bodies really need to sleep well. A shortage of melatonin can also occur when we lack serotonin, a key ingredient needed in the production of melatonin.

Serotonin - the ‘feel good’ hormone,

Like melatonin, serotonin is a neuro-transmitting hormone that, that is produced in the body. In addition to being known as the ‘feel good’ hormone, it is a vital building block in the body’s manufacture of melatonin. Insufficient serotonin leads to a shortage of melatonin, causing the sleep cycle to change.

Serotonin is important for our sense of well being, influencing our mood and regulating anxiety. A shortage of it is known to lead to depression, even suicide. It is therefore important to actively support our body to produce as much serotonin as it needs, not only to stay feeling good, but to produce the melatonin needed to regulate our body clock.

Luckily, there are steps we can take that will assist production of this important hormone.

Boosting serotonin, naturally

There are a range of pharmacological products designed to boost the body’s serotonin and melatonin levels, but listed here are simple interventions that could make these drugs unnecessary.

1. Food

Hippocrates declared, “let food be thy medicine”. It is possible for you to consume the foods that give the body what it needs to produce more serotonin and melatonin. Our bodies need is food which is rich in L-Tryptophan, a vital ingredient for the manufacture of serotonin.

Tryptophan is an amino acid that is typically found in the following foods: eggs, cheese, oily fish, whole grains, fresh dark greens, tofu, chicken, seeds, nuts, pulses and beans. And we don’t mean tinned baked beans, but the kind that you buy in health food stores that need soaking before you cook with them.

2. Daylight/outdoors

Daylight primes the body’s production of melatonin and serotonin. It helps to stabilise the Circadian Rhythm and makes us feel good, thanks to the serotonin boost. Being outside for even 15 minutes a day makes a difference. If you wear glasses, move them away from your eyes to avoid the glass filtering out certain frequencies of light needed to charge your system.

Being out in daylight, first thing in the morning, reinforces the start of the next 24 hour cycle.

3. Grounding

Modern lives have become more insulated from the Earth, thanks to the rubber soles on our shoes and spending most of our time indoors. Without this grounding connection, we can experience a build up of free radicals (positive ions) and static in the body. Most of us will have experienced a static shock when touching something metal or another person. This was an electrical discharge taking place between ourselves and the other object or person when we 'got zapped'.

To earth ourselves, all we need to do is make bare skin contact with the ground. Simply spending several minutes a day, bare foot on the grass, will allow static and free radicals to discharge from your body into the Earth. Even better is lying down on your back, without a pad or raincoat to insulate you.

Maximise your surface contact with the Earth, by bending your knees so that the soles of your bare feet can still make full contact as you lie on the ground. Try it for yourself and see how differently you feel after just 10 minutes.

Free radicals are known contributors of many diseases, inflammation and cancer. Research that shows that the neutralising effect of grounding not only helps to reset the Circadian Rhythm, but it can significantly reduce inflammation within the body.

4. Exercise

Exercise boosts tryptophan into the brain, where it is processed into serotonin and then into the melatonin which helps regulate the Circadian Rhythm. Exercise is also known to produce dopamine (another feel good hormone), and it 'burns off’ cortisol. Gym junkies have long recognised that a good workout relieves stress and can shift bad moods.

Alternatively, you could get the benefits by jogging, going for brisk walk, or following a ‘high intensity’ routine that involves push ups, planks and squats, etc.

High intensity routines can be built up gradually and require little space and time, yet they can provide a good muscle and cardio work out. These routines need only last 10-15 minutes and so can easily slotted into busy daily schedules. Don't make excuses, make time for them, because they help well-being.

5. Mindfulness/meditation

The practices of meditation and mindfulness have really caught on with the general public over the last 10 years. Science has shown how it boosts mood, functioning of the immune system, regulates emotions and supports the amygdala (responsible for our fight or flight reactions) to recover more quickly.

It also builds our inner spaciousness (equanimity) which makes us less prone to stress and reactivity and more likely to adopt wise, objective perspectives when challenged. It has even been recorded that the practice of mindfulness (intentionally noticing what/who is present rather, than being in our heads) helps to reduce the production of cortisol.

There are many apps, courses and books which offer guidance to how to meditate and outline different ways of practicing mindfulness.

6. Sleep Hygiene

Staring at screens or bright lights soon before going to bed postpones our clock rhythm, reducing the quality of our sleep. A golden rule is - no screens in the bedroom. If you find it hard to get a good sleep, lay off the telly, phone and caffeine for at least an hour before bed.

Create a ‘getting ready for bed’ routine. Perhaps include a warm shower, bath, reading or meditating in the hour before bed time. Make sure that there is minimal light getting into your room. Even though your eyes are closed, the body still perceives light and mistakes it for daytime. The brain then reduces the secretion of melatonin which is needed to stay asleep.

Consuming food or alcohol late in the evening activates the daytime processes of digestion. This impedes the nocturnal processes needed to mop up and repair muscles and cells after the day’s activities.

7. Time Restricted Eating (TRE)

Science experiments have revealed that eating also affects our body clock by activating biological processes which would normally only occur in daytime. Eating late is therefore unhelpful when you are about to sleep.

TRE is a highly effective way of restoring our Circadian Rhythm and boosting well-being. This means only consuming food and drink within a restricted window of time, ideally between 8-10 hours.

If you take your first mouthful of coffee or food at 8am, your last mouthful will be at around 6pm (assuming a 10 hour eating cycle). Water can and be consumed any time. Decaffeinated teas count as water, so long as no milk or sugar is added.

This can be one of the most challenging practices in your well-being arsenal, but it is one of the most potent. When you get into it, you won’t want to give it up. You might wish start gradually with an eating window of 12 hours, then shorten it by 30 minutes per week, until you get to the level where the benefits become exponential (sub 10 hours).

It is recommended that your eating window opens and closes at the same time each day, to entrain your body clock more quickly. This is also an aid to reducing jet-lag and adjusting to new time zones more easily.

Experiment to find the 'Goldilocks' window for you. You'll recognise it because you will start to feel and sleep better. Even if It takes several weeks of committed experimentation before you find what window works best for you, it is a worthwhile investment in your overall well-being.

Summary

Our Circadian Rhythm drives our body clock which in turn switches on the appropriate mental and biological processes at their appropriate time. When we live out of synch with this 24 hour cycle, the release of hormones that support sleep and wakefulness also fall out of step. It is then harder to feel at our best and to perform at our potential.

Preserving and living in accordance with our Circadian Rhythm is important for a healthy, happy and functional life. The guardians of that rhythm include cortisol and melatonin - we need both to enable the body clock function and be in balance with our environment.

There are a range of environmental factors that affect our body clock:

- Stress and life style habits can escalate cortisol to unhelpful and unhealthy levels.

- Melatonin is affected by diet, sunlight and exposure to blue light in the evening.

- Crossing time zones causes our Circadian rhythm to be out of synch with our destination

- Timing of caffeine, exercise and eating can affect our rhythm and our ability to sleep.

However, our body clock needn’t be a victim to circumstance. There are reliable steps that we can take to manage it and so optimise our sense of well being and performance.

These steps include:

- A diet rich in foods with L-tryptophan

- Exercise to burn off excess cortisol and to boost tryptophan into the brain

- Exposure to daylight, ideally outside but sitting by a window is at least something.

- Grounding, via daily skin contact with the Earth, to discharge static and free-radicals

- Practice meditation or even just mindfulness, to induce well-being and reduce cortisol

- Adopt an evening routine that prepares the way for a deeper, more nourishing sleep

- Follow a TRE routine, restricting your window of eating to 8-12 hours.

Hopefully this article will make you aware of your own body clock and how it drives your daily and biological patterns of being. Knowing this may encourage you to take more responsibility for its proper functioning.

Don’t delay. Develop your own daily practice that incorporates the 6 activities above, for boosting your serotonin, melatonin and rebalancing your 24 hour Circadian cycle.

www.dancehammer.co.uk